Teaching, etc.

Ekin Erar, Leyuan Li

A Look at the Classroom_March 2023

An Annotated Conversation Between Emerging Educators

Ekin Erar and Leyuan Li

Annotations by Mai Okimoto and Pouya Khadem

March 2023

What does it mean for writing to be a collaborative and discursive process?

The following text gathers a series of email exchanges between two friends, Ekin Erar and Leyuan Li—both emerging educators at U.S. architecture schools. During the Fall 2022 semester, they shared updates of their professional lives along with candid reflections of their respective teaching roles, providing a glimpse into the daily scenes in architecture academia.

As an annotated written conversation, the piece explored the slower temporality of the written medium. Through shared observations with Ekin and Li, editors Mai Okimoto and Pouya Khadem became indirect participants to their dialogue—perhaps traceable in its shifting tones. The editors’ notes developed independently to connect the text to recent events, disciplinary discussions, and policy landscapes. They read the conversation through themes of the position of adjunct faculty, architectural pedagogy, the predicaments of architectural academics, and the business of the architecture academy.

This conversation has been edited for length and content. The annotations reflect only the views and opinions of the editors, not of the participating authors.

Date: Oct. 18, 2022

From: Ekin Erar

Hi Li,

How’s your semester going? It's your last semester in Houston—must be bittersweet but also, exciting?

I just finished drafting the syllabus for my upcoming elective. How’s yours going? It’s a bit intimidating, writing a syllabus is like devising a pedagogical prompt: There’s pressure to decide what’s worth teaching for an entire semester, and to figure out how to integrate your proposal with the school’s overall discourse.

I visited the university’s Human Ecology department today because I wanted to familiarize myself with their resources (my seminar has a sewing component to it). They have great facilities and a strong textile department—it would be amazing to share technology and machinery between departments. The professor who gave me the tour said she couldn’t recall any collaborations between our two departments. Could be a good opportunity.

Tell me about yourself.

Ekin

Date: Oct 22, 2022

From: Leyuan Li

Hi Ekin,

Great to hear from you! I hope your semester has been going well.

The past few days have been hectic. I stayed up until 7:00 this morning to finish applying for a research grant in Hong Kong. Now that I have some time, I’m going over what I want to teach next semester. I love my cohort and my students, but I’m excited about what’s ahead. [1]

I don’t know about you, but I’m exhausted. I’m swamped with work, teaching two studios in order to satisfy the conditions for maintaining my visa status: A first-year studio from 9:00 to noon, and a second-year studio from 1:00 to 5:00 on Mondays, Wednesdays, and Fridays. Reviewing 32 projects in one day is intense. [2]

Most days I only manage to speak with half of the students, so I spend my Tuesdays and Thursdays responding to email questions from the other half—in addition to preparing for the next day’s classes. Virtual communication holdovers from the pandemic can be convenient, but they add pressure to make myself available outside of class to the students who didn't get an in-person critique. I enjoy working with the students, but I end up having less time for my own design and research even though I am aware how important that is for my career. And so I just stay up…Maybe this profession is not for me? I don't know. [3]

Tell me more about your seminar.

Love you,

Li

Date: Oct 24, 2022

From: Ekin

Hello!!

My seminar prompt is based on the project I worked on with a friend—we had submitted it to a biennale and it was selected as a finalist. While I was happy that the work was recognized, it wasn’t going to get built.

Receiving awards and recognitions can feel like pure luck sometimes, like winning the lottery. I often think about the self-exploitation that we put ourselves through in the hopes for winning commissions. Competition entries require so much free work that I’ve become fundamentally against the ones you have to pay to enter. I’m glad that I get to build a version of this competition entry at the university now as an exhibition, otherwise it was going to be another shelved project. xx

Teaching two studios is absolutely bananas. I can’t believe you are going through with it! I have no idea how anyone can critique 32 projects in a day. Do you do group desk crits? I’ve found it helpful to ask the students to critique each other’s works with me so that they practice thinking critically about their own projects.

How are things going with your work visa? I am a little worried about my status for next year, with no clear plans yet. Hopefully, renewing my visa will not be too complicated. [4]

<3

EE

Date: Nov 01, 2022

From: Li

Hi Ekin,

Yes—just as it's the case for competition entries, submitting essays/abstracts and applying for grants often needs to happen in the spare time. It often seems to be the only way to get ahead. [5] This year I’ve already applied and submitted to multiple conferences, biennales, and grants. I was lucky enough to have a few of my applications accepted, one of which is an installation at a biennale in Shenzhen that I’ve been working on for the past few weeks. The exhibition opens in less than a month, and I’ve been super busy. I’m still finalizing the design and trying to get in touch with contractors.

Speaking of my work visa, I’m glad that some universities are willing to sponsor visas for their employees with short-term teaching posts. However, the application process has been quite rocky. A few days ago, I received a notification from the government immigration department to submit additional evidence of my current legal status—letters from current supervisors, old paychecks, etc. I feel like I have to constantly prove to the immigration officer that I am a good, well-behaved foreigner. [6]

Best,

Li

Date: Nov 04, 2022

From: Li

Ekin,

I meant to ask you, how’s your exhibition prep going? How are you feeling?

A few days ago, I had some interesting conversations with my colleagues about the importance of students' involvement in academic mechanics, such as the faculty hiring process or studio review jury. When I was interviewing for fellowships earlier this year, a few schools included students in the interview process, giving them opportunities to voice their opinions and concerns. I think it’s great that this change is taking place; the student body generally seems to have stronger voices and involvement in the administration’s decision-making processes than we had when we were students. xx Is the mechanism of academia slowly changing, or are students better represented by student government or organizations? I am so happy to see that students are keen on proactively working with university administrators in shaping a more inclusive, diverse, and equal learning environment. Despite many student initiatives, I personally haven’t come across as many faculty collectives, at least not for the adjuncts. [7]

Anyway, just some random thoughts.

Li

Date: Nov 15, 2022

From: Ekin

Hello friend!

Sorry I’m late to respond. The exhibition is supposed to go up by next week so I have been running around trying to finish the construction. I’ve retrofitted the entry to the hallway—smaller budget, smaller project.

Preparation of Paperspace exhibition installation, Fall 2022, Cornell AAP.

I am sorry to hear about the visa struggle, I totally relate. Despite obtaining legal status to live and work in the U.S., I couldn’t leave the country for the past few years because of immigration restrictions—it can get exhausting to navigate the layers of conditions that one needs to maintain in order to live, work, and travel freely, especially without easy access to administrative, financial, and legal resources.

I’m also thinking about job applications, considering that I don’t have a position secured for next year yet. I worry that every time I get a new position, it will feel like I am starting over in an unfamiliar place, having to deal with the same stress of visas, finances, etc. In the past year, I’ve spent a good chunk from my savings just to stay afloat—moving expenses pile up. I don’t want to have to go through it every year. [8]

My school started a mentor program for fellows. In a recent session, we talked about the review format for studio work—and I realized that reviews can be what makes architecture school challenging for some students. While the review system provides students with the opportunity to practice discussing their work and receive valuable feedback, it also perpetuates a competitive environment. They feel the pressure to perform in front of each other and a group of "jurors"—the word on its own establishes an insurmountable hierarchy. [9] And the jurors also feel the need to give a strong performance. There is so much pressure to say the right thing at the right time.

Miss you tons,

Ekin

Date: Nov. 27, 2022

From: Li

Hi Ekin,

Final reviews are coming up in a few days, and my anxiety has been building over the past week. As someone who has always enjoyed giving feedback to friends and students on their work, I don’t know where my anxiety comes from. Is it fear of speaking in front of a large audience? Or is it my concern over how I’m perceived and evaluated by the others?

A few weeks ago, I attended a midterm review of a second-year studio covering housing and basic principles of design. It’s their first time designing a house, (which is likely what drew many of them to architecture in the first place). Loaded phrases like environmental activism, architectural autonomy, and hierarchy came up in the critique, and I couldn’t help but notice some students looked confused and discouraged. While I think discussing the external forces in tandem with architecture is valuable for students in upper-level studios, this instance made me question whether foundational studios need to concentrate on elementals before anything else.

I agree about the pressure for faculty to perform. It’s not uncommon in an architecture school review to see a juror steer the conversation away from the students’ work—and interesting discussions can surface (even if the students may not think so)—but sometimes it becomes a reviewer’s monologue. I’ve started trying out walk-through reviews, where reviewers move around and talk to students individually. The conversation format seems more relaxing, while remaining productive for both the students and the faculty. xx

You know architecture is charged with struggles, contradictions, and tensions—it’s unpolished, chaotic, and ever-changing. This is all amplified in the studio, where the lifespan of an architectural project lasts for a semester of sixteen weeks. Within this limited time, students are expected to come up with the polished imagery of a resolved project.

On the one hand, I want to make visible the unfinished and the unresolved, foregrounding them as a critical part of learning. On the other hand, I understand the intentions behind the pursuit of beautiful images that will come out of the final reviews—they will not only be promoted as the student’s work, but also evaluated as our own. I feel like a salesman.

What instructor wouldn't want to post these polished, curated images on Instagram? In many cases, the desire to publicly express pride for the students and their work (often stemming from a shared sense of co-authorship) becomes inextricable from external pressures to constantly self-advertise. Like the insurance companies that bombard potential customers with calls and emails, we make post after post on social media of beautiful model photos and renders, or the papers we’ve written, presenting ourselves as the future visionary builder. I feel the pressure to post my own design work as if the failure to keep up with others is a form of creative impotence. Where is all of this stress coming from? [10]

And so here I am, guiding my students over the finish line for final reviews. I find myself wanting to prove my competence by being one of the most beautifully curated studios, while still giving students the freedom to explore. I’m still learning how to let go of the pressure.

Good luck with your final review, Ekin!

Warmly,

Li

Date: Dec. 24, 2022

From: Ekin

Hi! Sorry I didn’t get to respond to you sooner. I was juggling exhibition disassembly and studio finals. My first finals are over, finally. It was a stressful experience to say the least, but very rewarding to see the students’ work come together.

When I was a student, I saw everything from my own perspective and wasn’t really aware that my work could become a piece in my instructor’s teaching portfolio. I think now that I am teaching my own classes, I try to see how students’ work can collectively fit in a broader research agenda of my own. xx

Happy holidays!

EE

Date: Dec. 29, 2022

From: Li

Hi, Ekin!

I agree about the change in perspective. I’ve noticed that a dedicated instructor has the potential to make the whole studio thrive, not just a few students. When an instructor invests time and energy—and fosters a supportive environment—students’ strengths and weaknesses become less of a factor in the studio’s outcome.

Students’ interactions with their peers also have a huge influence on their studio experience. I’ve been trying to foster peer collaboration, or at least, to have conversations about collaboration with my students—that they should always learn from each other and seek help from one another. The students—first-year and second-year undergraduates—seemed to embrace the spirit, but there would be a doubt, or lack of confidence towards their classmates’ feedback, and they end up returning to their instructors—whom they perceive to be the authority figure. xx As instructors, how can we help students develop critical thinking through collaboration?

Speaking of collaboration, I recently tried to collaborate with a few tenure-track faculty. We’ve talked about this before, but the tenure-track faculty seems to deal with a different set of pressures on their career journey from what we face. My understanding is that tenure track faculty have requirements to meet that at times make them prioritize individual work over collaboration. [11] This isn’t to say there’s no collaboration; I have seen many successful collaborations emerging in institutions, including a cross-disciplinary studio collective composed of faculty and students. The goal is always to cooperate.

Happy New Year! I’m sad that I won't be able to celebrate with you this year. I hope to scoop you next year in your new home.

Yours,

Li

Date: Jan. 24, 2023

From: Ekin

Hi Li!

Happy new year! I’m back for a new school year and it’s already very busy, although a few exciting things are happening. Firstly, congrats! Your lecture series line-up looks great. So happy to see so many of our talented peers lecturing—I’m sure the students will enjoy it. I’m also looking forward to your upcoming lecture.

I’m going through editing the final documentation of the exhibition—it was months of preparation and construction for a two week long exhibition, but now that it’s finished, I think it was totally worth the effort.

I hope you are settling in at your new position. It is quite a challenge to adjust to a new place while teaching. School requires so much brain power that you have no time left to yourself to reflect and relax, which I’ve learned is a big part of settling into a new home and city.

All the best,

EE

Date: Jan. 03, 2023

From: Li

Hi Ekin,

Glad to hear from you!

We just kicked off the lecture series, the first one was a great turnout. I am so glad that the college has been supportive of a lecture series that foregrounds young practitioners from minority communities.

Looking forward to the final documentation of your installation! I wanted to show you some images of the biennale installation—it has been quite an experience, but I’m happy that the installation has been actively engaging the domestic farming communities in China.

Setting up Balchen installation, Shenzhen Biennale 2022.

The show is going on, and will continue. I am so excited about your current projects and seminar, and looking forward to the challenges and adventures ahead of us.

Good luck with the semester. See you on Zoom soon!

Warmly,

Li

1. Advancing in the architecture academic career requires gaining recognition for works that are independent from teaching (as reflected in qualifications and application materials on teaching job listings). While it encourages academics to engage with their interests beyond the classroom, the need to gain recognition—and in extension the production of work to-be-evaluated, whether in the form of buildings, publications, or exhibitions—puts educators on a path of continuous grind, juggling teaching and additional school responsibilities with individual work. This echoes Byung-Chul Han’s concept of the achievement society (2015), in which “the achievement-subject gives itself over to… the free constraint of maximizing achievement. Excess work and performance escalate into auto-exploitation” (Han 2015, 11), and 24 hours is simply not enough to achieve it all.

2. In the U.S., having a full-time working status is a must for international educators who do not have permanent residence and are on employer-sponsored visas (see H1-B (worker visa) or J-1 (scholar visa) criteria on USCIS website). In a field where developing personal projects is a crucial part of career evaluation, international educators face legal constraints to working less than full-time.

3. Citing Luc Boltanski and Eve Chiapello’s work, Jonathan Crary in 24/7 Late Capitalism and the Ends of Sleep (2013) observes the ways in which technologies in contemporary capitalism have contributed to the merger of private and professional time—the merger of work and consumption—rewarding those who are constantly engaged, communicating, or processing within some telematic milieu (Crary 2013, 15). Not only have the digital technologies reshaped our attention, they have also curated an environment that encourages the achievement subject (borrowing Han’s term) to continue their self-exploitation.

4. Adjunct faculty without long-term job security—a condition that Alexandra Bradner has coined as “gig academy”—is a persistent problem in the broad academic field. Marianela D’Aprile summarizes this concept in Common Edge: “Non-tenured faculty in every discipline, and especially in the humanities, have increasingly numerous responsibilities and decreasing salaries, and it’s ever-more common for them to be offered short-term contracts with no job security beyond one or two semesters.” For visa holders, the fixed-term employment of adjunct faculty positions means they may need to update their visa status each time, involving legal fees, months of processing time, and the possibility of rejection by the USCIS (United States Citizenship and Immigration Services.) The selection process for the American H1-B work visa operates on a lottery system—a worker who meets all legal criteria may face rejection—while other work visas like the O-1 visa are awarded based on qualitative criteria.

5. In the piece "The Architect as Entrepreneurial Self" (2015), Andreas Rumpfhuber discusses how Hans Hollein's Mobile Office (1969) anticipates contemporary aspects of the architects’ “daily grind,” capturing the architects’ immaterial labor of producing “the informational and cultural content of the commodity” (Rumpfhuber 2015, 41). He argues that the entrepreneurial self emerges from the acceptance of “the prerequisite to expose oneself to the gaze of the other,“ and a reality in which living and working become one and the same.

6. A Google search of “adjunct faculty h1-b” will return mixed results, with some links to university pages showing they do not sponsor visas for those working in temporary or part-time positions. Despite the advocacy and commitment by many academic institutions towards greater diversity and transparency among the faculty population (in addition to the student population), they often don’t have the institutional framework in place to support foreign individuals entering the academic field. In contrast to the statistics of student demographics that are promoted on university websites, data on staff and faculty population tend to not be readily available.

7. Are there cross-institution organizations or initiatives for architecture faculty like there are for professionals in practice? If they exist, how active are they at individual institutions?

Preparation of Paperspace exhibition installation, Fall 2022, Cornell AAP.

8. For many, pursuing an academic career means pursuing one’s passion, but financial security is not always guaranteed. While complete information on the specifics of an institutions’ compensation system is often hard to come by, it is not uncommon to read about episodes of adjunct faculty in various academic fields juggling multiple jobs to pay their bills. A 2022 report published by American Association of University Professors (AAUP) reveals that part-time faculty members (of universities, liberal arts colleges, and community colleges) earned an average of $3,850 per course, and 65% of schools provided no health-care benefits to those adjunct professors.

9. In her Log 48 article, ”Not-Habits” (2020), Ana Miljački reflects on the norms (or the habits) that are ingrained in architecture education, asking what it would take to challenge the institutional norms that have “been deeply codified in our timetables, grading sheets, review protocols, hierarchies, and values” (Miljački 2020, 107). As part of an experimental design studio entitled Collective Architecture Studio, she and her students challenged the conventional “juridical call of the presentation format” of final reviews, identifying and removing the “hierarchies commonly inherent in final juries: specific authorship, privileged expertise, and the finality of our proposals” (Miljački 2020, 116). Miljački notes the reviewers’ receptivity towards adjusting their remarks and roles in response to the different format, as well as the valuable conversation that it sparked around the students’ work—suggesting that disciplinary change could begin to take place from inside the classroom.

10. While image has always been an invaluable component of architecture, academic individuals and institutions are under increasing pressure to produce and publicize “beautiful” images in high frequency, in order to establish their presence to their audience—prospective students, future hires, peer institutions and colleagues, etc. When these images come from students' work, do semester-long projects become something more than a part of an individual student’s educational journey?

11. As the myth of the "lone architectural genius" is increasingly put into question and institutions embrace the ethos of collaboration, what does the corresponding shift look like for the broader academic field and among faculty members? Classroom experiments such as Collective Architecture Studio's (discussed earlier in annotation 10) are important catalysts for broader disciplinary change—they can affect how students engage with others in the classroom, how they understand their work is evaluated, and even the work they produce. What groundbreaking experiments and ideas might we see emerge from classrooms (and beyond) when collaboration is fully sanctioned and encouraged by institutions?

Preparation of Balchen installation, Shenzhen Biennale 2022.

Crary, Jonathan. 24/7 : Late Capitalism and the Ends of Sleep / Jonathan Crary. London ;: Verso, 2013.

Han, Byung-Chul, and Erik Butler. The Burnout Society. Translated by Erik Butler. Stanford, California: Stanford Briefs, an imprint of Stanford University Press, 2015.

Miljački, Ana. “Not-Habits.” Log 48 (2020): 107-116.

Rumpfhuber, Andreas. “The architect as entrepreneurial self: Hans Hollein’s TV performance “Mobile Office” (1969).” in The Architect as Worker: Immaterial Labor, the Creative Class, and the Politics of Design. Edited by Peggy Deamer. London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2015.

Ekin Erar is an architect and designer, currently serving as a Design Teaching Fellow at Cornell AAP. Her work brings together image construction, material research, and analysis and recreation of assembly processes, through which she explores the relationship between the real and the represented.

Leyuan Li is a Chinese architect and educator whose professional and academic work focuses on interior and urban realms in the articulation of spaces and societies. He is currently a Visiting Assistant Professor of Architecture at the University of Colorado Denver.

The Right to Read

Matthew Allen

Who Gets to Write?_January 2023

Matthew Allen

January 2023

Consider that the Bill of Rights is a written document. “Congress shall make no law... abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press; or the right of the people peaceably to assemble...” There’s a tempo to reading. Do you find yourself absorbed in quiet contemplation? On a lazy afternoon it might go unnoticed, but cramped on a crowded commute, the active effort required to focus attention and sustain an inner dialog is inescapable. These moments of hard-won private reverie are crucial to public life. It’s not only that abstractions like democracy and freedom depend on concrete practices carried out in a chaotic public sphere—the practices create the public realm. Just as locally negotiated systems of shared cattle grazing created “the commons” as it was traditionally manifest, our ways of carving out space for reading set up contemplation as a public good, a shared resource.

The value of a thriving attentional commons (to use Matthew Crawford’s term) has been recognized by progressive reformers since the advent of modernity. Take, for example, a proto-modernist slogan neatly lettered above the bed in a relatively minimalist Arts and Crafts bedroom designed in 1897: “Seven hours to work, to soothing slumber seven, ten to the world allot and all to heaven.” What is “the world” in this scenario? Through a process of elimination, we can infer that it’s not work, not sleep, and not spiritual transcendence. The philosopher Hannah Arendt often spoke of “the world” as the realm of highest human achievement, populated first of all by works of art and literature, which she distinguished sharply from entertainment. I find it hard even to imagine having ten hours a day to devote to “the life of the mind” (the title of Arendt’s last book) or “arts and letters” (a thoroughly anachronistic concept), and so it’s difficult for me to gauge the contours of a thriving attentional landscape. It’s not simply that there’s not enough time to ingest information. A feeling of information overload already percolated in medieval monastic libraries, and a technological solution—encyclopedias—developed during the same period. The problem seems to be elsewhere: in the habits and habitats that provide us with the mental and physical resources to read and make use of that reading. Even if the quality of information and access to it has grown, the quality of attention at our disposal has been actively undermined. Social media is an obvious culprit, with legions of programmers tapping the techniques of behavioral psychology to capture every micron of attention. The attention economy is among the wildest frontiers of capitalist development.

Photograph of a bedroom by Liberty’s, 1897 in Interior Design of the 20th Century by Anne Massey

(Thames and Hudson, 1990), 16.

Thus the question of who can read—who has the time and attentional resources—has become one of the most consequential conundrums of our present era. The complexity only mounts in specialized disciplines like architecture. Following revolutions in linguistics, anthropology, and philosophy, architecture since, say, 1960 spent several decades as a highly erudite field—a field premised on reading and writing. The creation of PhD programs established a class of academic architects as professional readers, and, at the same time, the intrigues of French intellectual life in its poststructuralist heyday rendered difficult concepts as popular spectacle. Reading was edgy. All this was directly correlated with how design was conceptualized. Buildings could be subject to “close reading,” and a good project would have a tight “logic” and present a clear “argument.” On the insights of deconstruction a whole theoretical edifice was built featuring the slippery mechanics of language. Its focus on openness and indeterminacy encouraged the average architect to play along. (There’s no wrong answer in the absence of Truth and Authority.) If, since then, architects are reading less and bringing to it a different quality of attention, this also means that the foundation has shifted beneath a broad swath of basic disciplinary concepts. Maybe architectural theory as it was once understood has already collapsed.

Media theory can help us sort through the wreckage and rebuild. Marshall McLuhan wrote about hot media and cool media: the former provide lots of information but offer low participation (like reading a book or watching a film) while the latter have low information bandwidth but demand high levels of participation (like a group chat or a discussion seminar). McLuhan’s contemporary, Walter Ong, followed with an extensive comparison of literary cultures versus oral cultures. Perhaps humanity has gone from orality (in archaic cultures) to literacy (for the past few thousand years) to secondary orality (with the cool media of the electronic age) and most recently to secondary literacy (how we read text on our phones). Something of the return of certain features of oral culture—which is premised on communal, participatory sociality—was vividly prefigured by Superstudio’s collages of “nomads” (really: disaffected western youth) lounging on the Supersurface. The next step is to jettison the romantic yearning for a simpler form of life and try instead to learn from contemporary oral cultures. How do you organize a fruitful discussion? What are the parts of a good story? What guides the listener (or reader) along the way? Storytelling encompasses all sorts of practices: chatting things over to make sense of the world around us, project presentations and jury discussions, but also oration and demagoguery. (As with any other technology, the potentials of storytelling can be used to good or bad effect. Just think of the impact of the microphone on politics in the twentieth century.) The realm of the live-and-in-person has affordances and techniques that can counter trends toward exclusive expertise with an imaginary of public abundance.

Which brings us back to the attentional commons. Attention is usually seen as a resource to be extracted or a means of extracting some resource. Advertisers are vying for your eyeballs; reading is a means of gaining some proprietary knowledge. A Gestalt shift is required. Conceptualizing a right to read is not about reading more, but imagining a world in which reading thrives—and the most important result might be that space is made for collective life of a more deliberate, open, and satisfying variety.

Matthew Allen teaches theory and history at Washington University in St. Louis. He is the author of the forthcoming book, Flowcharting: From Abstractionism to Algorithmics in Art and Architecture.

A Neighborhood Within

Mai Okimoto

Who Gets to Write?_January 2023

Re. Buildings

Mai Okimoto

January 2023

The ubiquitous low-rise office buildings that line Houston’s sprawling network of commercial corridors are a case study in an architecture of economic efficiency. Catering to diverse tenants, this typology has for decades offered flexibility and scalability—though often at the cost of overly sterile designs that say little about the tenants and their cultures. One is left with the impression that profit maximization inevitably locks this typology into the production of formulaic spaces with little formal variety, steering clear of untested or unnecessary spatial explorations.

Typical of Houston’s low-rise office buildings of this era, Corporate Plaza’s north and west façades are clad in mirrored glass. Less common are its east and south façades, which feature brutalist-like vertical bands that resemble pilasters.

7001 Corporate Drive in Houston’s Chinatown is a modest three-story office building that diverges from its typological cohort. At first glance, Corporate Plaza (built in 1980) does not appear to stand out from other buildings of the same typology. A closer inspection, however, reveals a calibration of density and scale that considers the tenants’ spatial needs, as well as moments shaped by feng shui, the traditional Chinese practice of arranging objects and space to be in harmony with their environment¹. Contrary to what one might infer from its name, Corporate Plaza is a conglomeration of tightly packed rental office units with a level of intimacy more common among apartment complexes.

Except for the pair of stone lions guarding the front entrance and the large red signage reading 華埠大厦 (”Chinatown Building”), the exterior of Corporate Plaza looks like a typical low-rise office or institutional building constructed in the second half of 20th century throughout the U.S.—the kind of unremarkable commercial remnant that one drives past without a second look. Yet past the lions, the building’s interior reveals another identity—one that resonates more closely with the sense of locality or community that comes through its other name: “Chinatown Building.” Its surprisingly compact scale and incorporation of oblique relationships are present from the entrance—the presence of a neighborhood further articulated by the display of disparate signages and artifacts of the tenants.

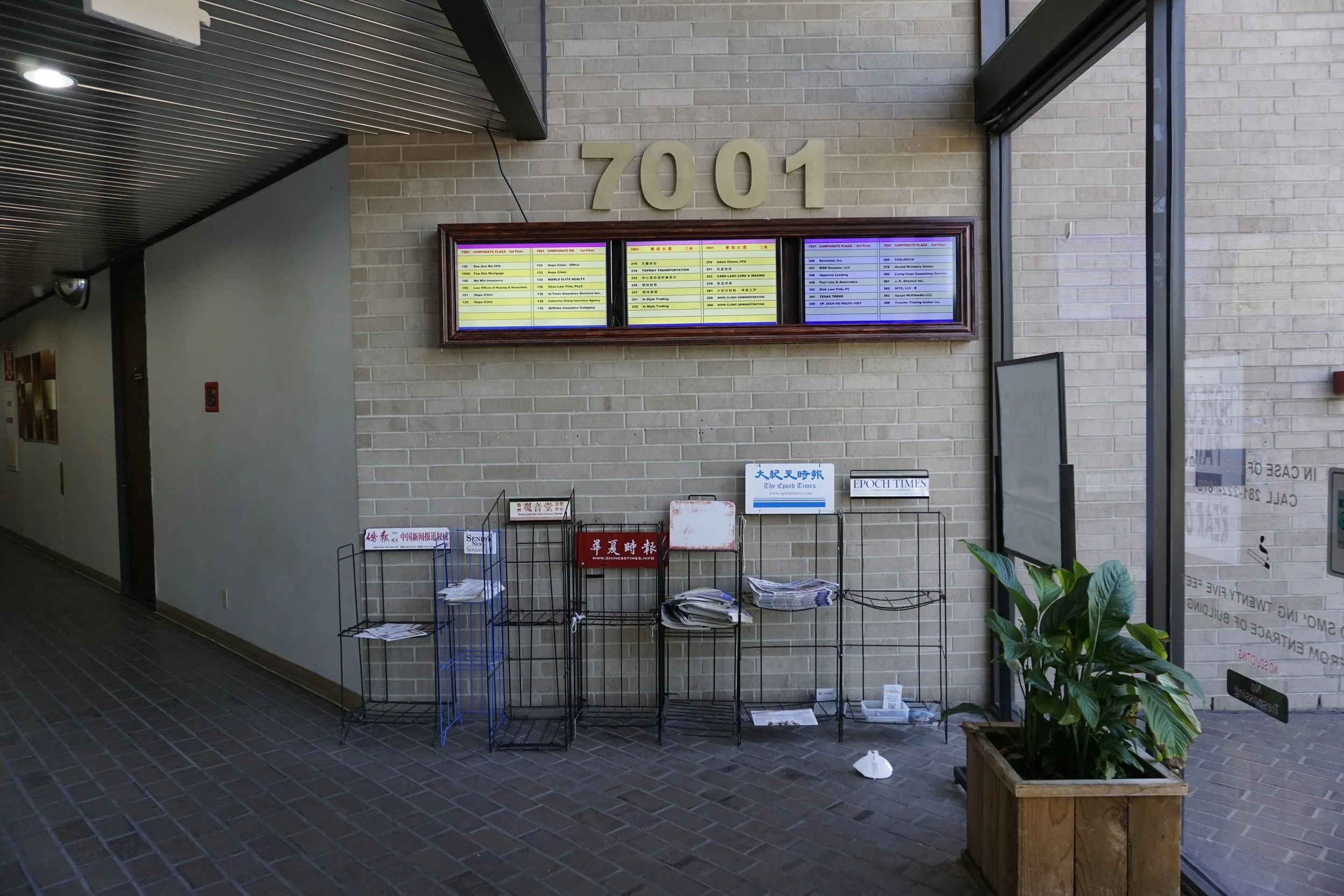

Within the vestibule, objects such as bilingual newspapers, tenant directory monitors, and a whiteboard for handwritten announcements bridge the building’s interior and exterior.

Behind the entrance doors, visitors step into a tall, narrow vestibule, where they are greeted by stands of Chinese and bilingual newspapers and a row of monitors displaying the tenant directory. With a slight turn (a move intended to dispel negative qi, which is thought to travel along straight lines) and a ceiling drop, the vestibule compresses into a dimly lit, narrow corridor. Cutting diagonally through the building and functioning as its spine, the corridor, connects the front and secondary entrances, and orients the building along its northeast-southwest axis. At the center of the diagonal spine is an atrium with a skylight, providing a natural light source into the building’s deep interior, as well as an opening for the qi to flow through the building.

The diagonal spine of the corridor expands into an atrium, which offers pockets of spaces partitioned by the circulation core and framed by greens.

The atrium, warmly lit through the skylight and fully enclosed on the upper levels by glazing on all four sides, feels small for an office building of this scale. Looking around, company names and phone numbers are laminated onto the windows here and there; the mix of English, Chinese, Vietnamese, Korean signs advertising law firms, travel agencies, and financial services offer glimpses of the buzz of activity taking place behind closed blinds. The garden and a running fountain—elements considered to bring prosperity and luck in feng shui—together with rows of mailboxes suggest an inner courtyard of an apartment complex, rather than an office atrium.

Compact office units form a dense mass around the open atrium, creating two contrasting spaces on the building’s upper levels.

At the atrium’s center are a pair of elevators enclosed in a decorated shell and a switchback staircase clad in white painted metal. The vertical circulation elements anchor catwalks that cross the atrium on the upper levels, echoing the diagonal spine running northeast to southwest on the ground floor. On the second level, the diagonal is carried from the building’s center to its periphery by the atrium catwalk, which transitions into a double-loaded corridor inside the mass of the building. The circulation diagonal is contained within a square; the double-loaded corridor makes a turn at the intersection to continue tracing the square offset from the building’s edge. Moving from center to periphery, the open and spacious atrium quickly disappears from sight. The identical doors of private offices appear one after the other on each side of the hallway and crowd the field of view.

Most of the rentable area consists of spaces ranging from 700 sq.ft. to 1,600 sq.ft. with the smallest leases starting at 300 sq.ft. While there are several larger suites, the interior parceling was likely designed with the businesses of recent immigrants in mind, often operating with a small workforce hailing from countries where population densities can exceed that of the U.S. by a factor of ten or more².

While private, the building is not anonymous, and has an atmosphere of a neighborhood or a community that is often observed in domestic spaces and smaller stores. In addition to elements that express the tenants’ presence, factors like the guiding design principles introduced by feng shui and the general disposition towards higher density and smaller scale have made Corporate Plaza into a low-rise office building that subverts typological expectations and is more than the capital returns of its real estate. It provides a space of community with a decidedly humane scale and composition.

Beyond its widely-popularized use in home interior decor, feng shui principles may be used to determine the orientation and configuration of buildings. Its practitioners seek to achieve a positive flow of qi, the Daoist concept of life energy, in order to invite good fortune and ward off bad luck.

One study indicates that per capita office space in Asia averages 100 sq.ft. compared to 140 sq.ft. in the Americas.

Mai Okimoto edits for the Architecture Writing Workshop. She works as an architectural designer in Houston.

While each month will have a dedicated theme, we also want to read about and share the beautiful, ugly, nice, terrible, weird, cool buildings/spaces that we have come across. Who gets to write? Who wants to write? Write to us (architecturewritingworkshop@gmail.com) if there is a building/space that you want to share. Write as much or as little as you’d like—we only ask that you have visited the place.

On the Economics of Writing (About Architecture)

Stefan Novakovic

Who Gets to Write?_January 2023

Stefan Novakovic

January 2023

I: Writing for a Living

I started writing for a living by accident: It was in 2015, my last month of college as an unexceptional English major with no plans after graduation, that I decided to write about cities and began my research. My brother, an architect, pointed me toward Urban Toronto, a niche news site covering the city’s development industry. I saw their call for interns. Saddled with student loans, moving to New York City for an unpaid internship was out of the question. But if this was less prestigious (and less competitive), it was closer to home—my parents’ home in Toronto, anyway, where I would be living after graduation. I gave it a shot.

I was thrilled. For three days a week, I wrote about urban development. The other four days, I worked a minimum-wage job in the gift shop at the Libeskind-designed Royal Ontario Museum, where even the floors were slanted. I preferred the writing. And so I learned as much as I could. I bought all the books on urbanism, architecture, and Toronto that I could find. At the end of the summer, the publishers at Urban Toronto offered me their assistant editor position, $1,500 a month. It wasn’t much, but more than I was making at the gift shop. I said yes.

Back at my desk, still shaking with excitement, I ran the numbers. $18,000 a year was less than minimum wage, and legally, I wouldn’t have a “job”—I’d have a full-time gig, with all the responsibilities of a permanent position and all the rights of a freelancer: a real journalist.

Urban Toronto had been founded as an online discussion forum—citizen journalism for architecture geeks in the early 2000s. By the time I joined, the website had been bought by a publishing company and had a mandate to produce daily news about development proposals or construction projects across the city.

This meant sifting through thousands of pages of public records, zoning applications, renderings, architectural drawings and urban planning rationales; I learned about architecture through the civic bureaucracy. Over two-and-a-half years, I attended about 50 community meetings and dozens of housing protests and organizing events. I would often write two or three posts a day at a twelve-hour turnaround.

In 2017 I began my first job in traditional architectural publishing, working as the assistant editor at Canadian Architect magazine and its sister publications, Canadian Interiors and Buildings. At $35,000 per year, my “job” was, legally speaking, another full-time freelance gig. The magazines were legacy print publications dating back to the mid-twentieth century, and had been part of Conrad Black’s media empire. By 2017, they were run by an independent publisher on a shoestring budget.

Although I did little serious writing—to get any meaningful writing opportunities, I wrote ad hoc print articles with no extra pay—my two years with Canadian Architect helped me learn the business—how press releases and publicists shaped the media landscape, and how magazines prioritized coverage. Reviews of new projects were the backbone of trade magazines; for a building or a book review to be published, it had to be pitched. The kind of on-the-ground, public record journalism I had learned at Urban Toronto was anathema.

After Canadian Architect, I became the web editor at Azure, a magazine that covers architecture and design internationally. For the first time, I had a real job with dental insurance—and enough money to pay the rent. Today, as Azure’s senior editor, I’m able to carve out more room to write and publish what interests me. With a monthly allocation for freelancers, I read and consider numerous pitches from writers with interesting ideas.

II: The Business of Writing

Success is often as much a function of industry savvy and shrewd networking as it is original thinking and good writing. Every magazine is delivering a product to a consumer. Publications like Architectural Record, The Architect’s Newspaper, Metropolis, Architect and Canadian Architect are considered “trade” or business-to-business (B2B) publications. Their advertising is aimed specifically at architects and designers—product specifiers. Instead of sneakers and Snickers bars, you’ll see bathroom fixtures, windows and doors, office furniture, lighting, high-end kitchens, etc. This economic reality shapes the nature of a magazine’s content and how they present it.

If more mainstream consumer media give you tips for renovating your kitchen, trade magazines give you tips for renovating other people’s kitchens. Only, when you’re writing for a professional audience, they are never “tips”—they’re examples of new and emerging trends or design philosophies. The tone differs, and so does the perspective.

When advertisers are looking to sell door handles and ceiling baffles to industry insiders, they don’t want to see their audience insulted—or even challenged. So the mandate for trade magazines often errs on the side of celebrating design rather than critiquing it. (Twenty years ago, when many trade magazines were still filled with ads for Cadillacs and credit cards, there was less concern about losing revenue through criticism.) While there may still be room for intelligent, critical writing in these publications—The Architect’s Newspaper does a particularly good job—it’s not their bread and butter.

While trade magazines offer occasional opportunities for serious critical writing towards more established writers, it’s a hard door to open, if it budges at all. Let’s say a writer has an idea to review a new public space in their neighborhood that really works (or doesn’t), or they want to investigate whether the buttons they push at a crosswalk actually do anything. Maybe there’s a compelling building in their city with a story that hasn’t been told. Pitches like these are more likely to be published by “consumer-facing” design media, like Curbed or Bloomberg CityLab, than by B2B publications.

Alternatively, a writer wanting to critique aspects of architectural practice or discuss the ideas of Manfredo Tafuri, for example, will likely find a better reception in subscription-funded or non-profit publications like Failed Architecture, Common Edge, and the New York Review of Architecture (NYRA). For a new writer, the best place to start these days might be the New York Review of Architecture; in particular, NYRA’s weekly Skyline newsletter offers a great opportunity to write a short piece or “dispatch” about a recent lecture or event. Unlike trade magazines, these publications don’t rely on advertising revenue, and unlike more mainstream design media like Curbed and CityLab, they don’t rely on a mass audience. This means they can serve a smaller, but highly dedicated readership, and produce critical, irreverent, and creative journalism that engages with theory, materialism and global flows of capital.

III: Writing and Class

Architectural writing rarely provides a decent living on its own. Very few people work in the field full-time, and those of us who do are almost invariably burdened by a volume of “content” and administration that makes thoughtful, meaningful work difficult. (In David Graeber’s Bullshit Jobs, in-house magazine journalists self-identified their work as a quintessential example of useless “box ticking.”) And while it’s easy to romanticize its quixotic nature, architectural writing faces the same existential crisis as journalism writ large: It just plain sucks.

When a career path is no longer financially viable, it becomes a job for rich people and limits the talent pool. That’s what happened to journalism. But to make matters worse, architectural writing relies heavily on what sociologist Pierre Bourdieu described as “social and cultural capital.” If you know how to speak the language of the publishing industry—often gatekept through jargon learned in elite schools—then success can look easy, especially if you’re not worried about money. But if you’re working a demanding, full-time job (or more than one), when will you find time to write? And if you didn’t go to a prestigious school or live in a major city, opportunities to get your work published can feel especially scarce.

I’m still here because I believe in the power and beauty of writing. It is a privilege—and a thrill like no other—to be able to share thoughts with the world, and to see them come alive. That’s worth embracing, too. And as hard as it is, it doesn’t take much to start: Each day, I try to write a good sentence. And then I look for the next one.

Stefan Novakovic is a writer and editor living in Toronto. You can reach him at stefan.b.novakovic@gmail.com

Speaking of Writing

Scott Colman, Sydney Shilling, Brittany Utting

Who Gets to Write?_January 2023